Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2024

© Jack Davis, 2024

A Major Research Project

Presented to Toronto Metropolitan University

Master of Digital Media

In the Program of

Digital Media

Jack Davis

BA, McMaster University, 2022

AUGUST 2024

Obscured Materiality: An Aesthetic Outlook

ABSTRACT

OBSCURED MATERIALITY: AN AESTHETIC OUTLOOK

Master of Digital Media, 2024

Jack Davis

Master of Digital Media, Toronto Metropolitan University

This thesis examines the implications of digital transformation within culture, specifically focusing on the evolving relationship between art, value, and materiality in the digital age. While the inherent human impulse to create, recognise, and appreciate art remains constant, traditional notions of materiality are obscured by unique characteristics of digital technology, including fluid technologies, cyber-physical convergence, and perfect reproduction. This work analyses attempts to reconcile digital art within the consequences of obscurity and proposes two aesthetic frameworks, dust armour and moth media. By exploring these frameworks, this thesis seeks to illuminate the emergent aesthetic possibilities of our increasingly digitised world.

Keywords: Digital Art, Art, Dust Armour, Moth Media, Fluid Technologies, Cyber-physical convergence, Frame, Social Media, Culture, Interactive Art, Exhibition, Gallery, Multimedia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have known for a long time that it is the people who make everything truly worthwhile. I would like to take this opportunity to thank some of them for their support. I could not have done this without them.

First, my sincere thanks to Dr. W. Michael Carter, Namir Ahmed, and Dr. Lorena Escandon. Their patience and guidance allowed me to focus my passions and expand my horizons.

Next, I must extend my gratitude to my cohort. These individuals not only were a constant source of support and validation, but quickly became cherished friends. They will remain as such.

Finally, I must thank my parents. Their unyielding love and support carried me through, I am forever grateful.

DEDICATION

I, who came before, dedicate this to you, who are the future.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

AUTHOR’S DECLARATION ii

ABSTRACT iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv

DEDICATION v

TABLE OF CONTENTS vi

LIST OF FIGURES viii

1.0 INHERENCY 1

1.1 Empathy 2

1.2 Materiality 3

2.0 FLUID TECHNOLOGIES 4

2.1 Technological Anxiety 6

2.1.1 On AI

7

3.0 CYBER-PHYSICAL CONVERGENCE 9

4.0 PERFECT REPRODUCTION 10

4.1 Making Digital Art Definitive 11

4.2 The Rejection of Replicability 12

4.3 Reframing Replicability: Neo-Ukiyo-e

13

4.4 The Embrace of Replicability 14

5.0 DUST ARMOUR 18

6.0 MOTH MEDIA 19

7.0 RIVULET, A CONCLUSION 23

REFERENCES 29

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. blodheaven [@blodheaven]. thank you kalos. 15

Figure 2.scrolling.end [@scrolling.end]. 16

Figure 3. verylovingcat.jpg [@verylovingcat.jpg]. 17

Figure 4.Jahangir, A. [@AmaanJah]. fool's paradise. 21

Figure 5._happinesseverydayimhappy [@happinesseverydayimhappy]. 23

1.0 INHERENCY

Culture, in its many iterations throughout history, has always been intertwined with art. Although thousands of years old, the cultural traces of Palaeolithic humans remain in their bone sculptures, carvings, and wall paintings. These artefacts provide a glimpse into the communities of ancient humanity and perhaps also the personalities, values, and interests of the individuals who once belonged within.

Although archeologists are uncertain of the exact motivations behind the creation of these artefacts, whether it be for the pleasure of aesthetic expression or for a more practical reason, in the present we are able to revere these artefacts as art (De Smedt & De Cruz, 2011).

In the modern day, motivational influences and context are often essential to the understanding and enhanced appreciation of art. Information regarding the artist’s personal life, the state of culture or society they lived in, and previous art proceeding and succeeding them, all contribute to our perception of art. While these ancient humans left behind no written records related to their works, there still exists context to those observing them in the present (De Smedt & De Cruz, 2011). These artefacts are the beginning point of all art found in the modern world, they are contextualised when observed as precursors of all art that came after, up to and including the modern day. The beauty we find in these objects comes in an act of empathy: we can relate to a human tens of thousands of years in the past, bridged by the shared desire to create (Lyons, 1967).

The archaeological record shows that these artistic behaviours emerged independently across geographically divided groups of ancient humans, suggesting that quality of creativity and the act of artistic expression is something inherently found in humans (De Smedt & De Cruz, 2011).

The question of why humankind holds this inherency and are driven to create, recognize, and value art, remains a notable topic of discourse in literature. Hegel (1975) suggests that art is the result of the human spirit striving for satisfaction in an existential existence (as cited in Lojdová, 2019). Similarly, Jean-Paul Sartre (1948) puts forth that the principal motive of artistic creation is the need for humans to feel someway essential in relation to the world, but is countered by Catherine Rau (1950) as she suggests that this is an awkward way to explain the fact that simply: humans take pleasure in making things. Determining which theory holds the most merit is largely irrelevant to this work. What rings true across these theories, and an integral assertion put forth in this thesis, is that art is a fundamental trait within the human experience.

1.1 Empathy

In its place as an inherent human trait, art is not only an act of creation, but also an act of empathy. As a viewer, in a gallery, or in any other context in which one would encounter art, the mere recognition of something as art implies also the recognition of the creator behind it. The recognition might not always be a conscious one: in the absence of an artistic statement, the viewer is left to ponder the motivational influences of the artist, for better or worse (Dewey, 1958). As a person views a work of art, their perception of the work is influenced by their own cumulative experience with art; gaps are filled and personal connections made. Perception of art from the viewer, is built subtly, and never without influence from other humans.

Conversely, as an artist creates; it is also never without the recognition of other people. This recognition may arise because the work in progress is a commission piece or is intended to be shown in a gallery, and will be influenced by the expectations, tastes, and critiques of the intended audience, consciously or unconsciously shaping the artist's choices throughout the creative process. Alternatively, the recognition could be the omission of these factors; by choosing to avoid the possibility of the work being viewed by others, the artist is acknowledging and thereby also directly influenced by other humans with their attempt to prohibit their viewership. If an artist is creating a work for practice, or for pleasure, they are still guided by the influence of human trends, techniques, and technologies. Empathy, in the sense of recognizing the multitude of humans behind any given artworks, is essential in the process, the perception and in the understanding of art. Didier Maleuvre (2016, pp. 17-18) asserts caution regarding the mistake of reducing the experience of art to solely the appreciation of the physical. He posits that works of art, in their physical form, are merely representations. To propagate this, one would be committing the pathetic fallacy: “the mistake of attributing an emotion to the object that evokes it rather than the person who feels it” (Maleuvre, 2016, pp. 17-18). The essential aspect of art lies outside of the physical, and in the encounter of art. The evaluation of the encounter of art, and its beauty found by the beholder, is not solely a cognitive process. Rather, the determination of beauty happens by means of the imagination, and therefore cannot be anything other than subjective (as cited in Kant & Walker, 2007). In this subjectivity, is where humans apply this empathetic link to other humans, thus determining their experience with art.

1.2 Materiality

To encounter and evaluate art is not simply to access it in a physical way. An encounter with art and the evaluation of its beauty, in essence, is derived from the recognition of its materiality. The concept of materiality, as described by Christina Murdoch Mills (2009), broadly encompasses any and all relevant context related to the work of art. This interconnectedness that is defined as materiality, forms the very foundation upon which we understand and value art in all its forms. It is a concept that transcends specific mediums or movements, speaking to the ability of art to connect humans through their empathy and subjective experience to something more profound than just physical representations.

In the present era, culture has undergone a digital transformation. The inherent desire to create art, and the recognition and value derived from the materiality of art remains constant during this stage of change. In the present era, culture has undergone a digital transformation. However, impulses to impose familiar aspects of materiality onto digital art often fall short, obscured by the emergence of fluid technologies, cyber-physical convergence, and perfect reproduction. This work evaluates attempts at the mitigation of these phenomena and posits the subsequent emergent aesthetic frameworks of dust armour, and moth media.

2.0 FLUID TECHNOLOGIES

The ubiquitous integration of digital technology into contemporary life necessitates a framework for understanding its impact on human behaviour and perception. This work proposes the term fluid technologies to describe the seamless integration of the internet and personal devices into daily routines. Building on Marshall McLuhan's (1964) concept of technology as an extension of man, fluid technologies enable a further evolution where the digital realm is no longer experienced as a separate entity but rather as a continuous extension of human action, behaviour, emotion, and thought. This fluidity arises from the intuitive nature of these technologies, both in hardware and software, which have become so ubiquitous and user-friendly that they effectively become seamless in everyday experiences. If the actual physical hardware is an extension of our body, then software is an extension of our conciseness.

The ways in which art first comes into contact with fluid technologies can be traced back to the photograph. Art critic John Berger famously argued that the camera, through its ability to endlessly reproduce images, fundamentally transformed our relationship with art. No longer confined to specific times and spaces, art became something that could be easily copied, disseminated, and consumed, further blurring the boundaries between the physical and digital realms (Bruck & Docker, 1991).

This shift, Berger argued, changed how we perceive and value art, moving away from the essence of the original and towards a more fragmented and reproducible experience. This concept of technology fragmenting experiences, extends far beyond photography or art to encompass the digital age as a whole (Bruck & Docker, 1991). The rapid rise of short-form video platforms like TikTok exemplifies this shift, as over a billion users now engage with a constant stream of content on these platforms (Montang et al., 2021). TikTok embodies what Guy Debord (1967), in his critique of modern society, defined the spectacle - a system where relationships between people are mediated by images or representations, leading to a sense of alienation and a detachment from authentic experience (as cited in Debord et al., 2021). An expansive feed of algorithmically curated and commodified videos aligns with Debord's concept by encouraging passive consumption over active engagement. This trend is further fueled by the very nature of short-form video, which, as Gurtala and Fardouly (2023) concluded after reviewing existing research, caters to shorter attention spans and a desire for easily digestible content. The result is a social media landscape saturated with short-form videos, as platforms like Instagram and YouTube have followed suit, incorporating their own short-form video features to compete for users' increasingly fragmented attention.

While users can produce their own content to share to a vast audience, they do so within the predetermined formats and trends dictated by the platform itself, reflecting Debord's observation that even seemingly free choices within the spectacle are often illusory. Users, seeking validation and engagement, often conform to the dominant trends and expectations of the platform, potentially obscuring their own unique voices and perspectives in the process. Community is found, and authenticity is valued, but is difficult to discern (Stroh, 2015). The appearance of freedom is thus an illusion, masking the underlying power dynamics and commercial imperatives that influence digital spaces. This constant stream of images and representations, while immediately gratifying, is ultimately fragmentary by means of saturation.

When art is readily available in these streams of short-form videos and placed between media, both similar and otherwise, its ability to capture our attention and leave a lasting impression is challenged. The ease with which we can scroll through countless images, videos, and sounds risks creating a sense of indifference, even as we might still crave meaningful engagement with creative expression. Social media, in its ability to mass-distribute short-from video is a fluid technology impactful to art. The result is a tension between accessibility and impact, context is lost, and materiality lessened in the process.

2.1 Technological Anxiety

The emergence of new technologies has consistently ignited anxieties about their impact on art and culture, often manifesting as moral panics that reflect deeper fears about societal change. From the printing press to photography, each innovation and subsequent movement has been met with resistance, accused of undermining artistic integrity, devaluing human skill present in the act of creation, or corrupting the very essence of creative expression. When photography emerged in the 19th century, it was met with scepticism. Rather passionately and among other critics, Charles Baudelaire considered photography a soulless mechanical reproduction, a trick, and alien to art (Franscina, 1983). As impressionist artists revealed paintings made atypical in appearance, and by unconventional materials, critics such as Félix Fénéon claimed the style to be simple-minded and reactionary (as cited in Herbert, 2007). Modern electronic music, as it was emerging in its modern form, received criticisms like those given by Jean-Charles François (1990), who claimed that the performance of electronic music reduced artists to mere trigger devices in comparison to the dynamics found in traditional acoustic performance.

In essence, these critics were convinced they saw the disappearance of materiality in their once familiar art forms. Technology, as it was integrated into existing art forms, obscured the materiality once easily recognizable. Today, these criticisms appear shortsighted, and in some cases, ignorant. Photography flourishes in its popularity and public appeal. The Impressionists are now hailed as revolutionary, their works profound in their subversion (Herbert, 2007). Electronic musicians, producers, and DJs are not only influential in modern music, but also in some cases, like that of the revered J Dilla, actively use the aesthetics of loops and trigger devices to produce and perform music (Stevenson, 2024). Materiality was not entirely removed from the medium, but rather the new technologies and subsequent new methods translated previous notions of materiality into new forms, expanding the medium.

2.1.1 On AI

When evaluating modern emerging technology, it is important that ignorance does not halt the search for shifted materiality. However, the emergence of generative artificial intelligence (AI) presents a challenge of a different order, one that transcends the anxieties provoked by earlier technological shifts.

The attempt to explain fully the impact of AI is futile and instantly incomplete. Development is so rapid that publication cannot keep pace(West & Burbano, 2020). It's not simply the arrival of a new tool, but a promise of the potential to fundamentally change all existing notions of authenticity, beauty, and creation. While previous innovations expanded the artist's toolkit or altered modes of creation, AI art generation hints at a future where the artistic process itself might become detached from direct human experience.

It's crucial here to distinguish between generative art as a concept, and the implications of modern AI-driven generation. Artists like Brian Eno have long used rule-based systems and algorithms to create, ceding some control to chance or computational processes (Gradim & Pestana, 2021). But crucially, these systems are conceived and set in motion by the artist, their vision guiding the output. AI art generation, in the potential and impending capabilities, threatens to conceal even this level of authorial intent.

Generative music is an effective area to explore this distinction through.

“Generative music is commonly agreed to describe music in which a system or process is composed to generate music rather than the composition of the direct musical event which will result from that system. The generative composer has only indirect control of the final musical result, and the creativity of the compositional process is found in the decisions about how the system will operate and the rules inside the system”(Rich, 2003, p. 17).

Wind chimes can be used to explain a key idea in generative music: its materiality is shown from the recognition of both the process and the result. The chime craftsperson carefully chooses materials and design, assembles the wind chime and places it in their garden (the process), which then creates beautiful sounds as the wind blows (the result). There exists a certain contract we hold with art, wherein we expect a human artist, or an equivalent human process, to be behind the art in either the process or the result. Now when an AI system can generate breathtakingly beautiful images indistinguishable from human-made art, and with the extent of human involvement unverifiable, we are faced with a profound uncertainty.

Both social media and AI-generated art are prominent examples of fluid technologies which enable difficulty to discern the intention and result, due to their capacity to provide passive access to create and consume art.

3.0 CYBER-PHYSICAL CONVERGENCE

The increasing fluidity of technology has lessened the distance between the digital and physical realms which influences and oftentimes, becomes, the daily lives of many. While the early internet primarily existed as a separate, virtual space, we are now witnessing a merging of the digital and physical, where the internet's influence extends beyond the screen and into the tangible world. Concepts and perception received from social media are now placed unto physical, real world things. This becomes cyclical, where physical events or experiences are considered about how they may appear online. The lines become blurred between personal and shared experiences, transforming how we perceive and relate to the world, both physically and virtually. These lines converge and the result is a cyber-physical convergence.

The desire to capture and share experiences online, has shifted the focus of audiences from quiet contemplation within gallery settings to creating shareable content. Galleries themselves, once confined to physical spaces, now maintain robust online presences, showcasing artworks and engaging with audiences globally. Some galleries have made efforts to encourage audiences to document and share media of the displays, while some ban photography of all kinds (Siemens, 2021). However, the convergence goes beyond mere online representation. Artists' careers are often judged and shaped by their social media presence, confusing the difference between artistic merit and online popularity. (Watson. et al., 2022). The perception of art, from both the perspective of the curator, viewer, and artist, is determined by cyber-physical convergence.

Timothy Morton (2013) coins the term hyperobjects, used to refer to things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans. The internet, with its global reach, and continuous evolution, can be considered a prime example of a hyperobject. Instances of human behaviour, tendencies, relationships, communication, and art, are all placed into this hyperobject, expanding across time and reaching across space, and ultimately becoming intertwined with each other. Humans are able to become close to the internet as a hyperobject, due to the access enabled by fluid technologies. The result is an extension of not only human ability, but also human consciousness. Cyber-physical convergence is the psychological effect of the societal ubiquity of fluid technologies.

4.0 PERFECT REPRODUCTION

A key aspect of traditional materiality is authenticity. To know a work of art is the original provides value to the art as an object, and reverence to the encounter of art. Walter Benjamin (1935), acknowledges that technology has the ability to undermine this aspect of materiality, in its ability to reproduce art.

Benjamin argues that in principle, a work of art has always been reproducible (Benjamin & Jennings, 2010). He acknowledges that copies of artworks have existed throughout history, whether created by students honing their skills or artists refining their craft. However, Benjamin distinguishes mechanical reproduction as a fundamentally different phenomenon. Unlike earlier forms of copying, mechanical reproduction generates copies that are nearly or entirely indistinguishable from the original. This process, Benjamin argues, diminishes the value of the original artwork by removing its unique presence in time and space, which is profoundly linked to its originality and authenticity (Benjamin & Jennings, 2010). Perfect replication is an inherent attribute and capability of digital art. This aspect of digital art presents a significant challenge to traditional notions of authenticity and, consequently, materiality.

4.1 Making Digital Art Definitive

While Benjamin was referencing mechanical reproduction in the context of the mechanical press, his notions regarding reproduction are heightened in the age of digital reproduction (Davis, 2023).This challenge to authenticity is further heightened by the inherent lacking of physicality of digital art. Unlike physical artworks, which derive a degree of uniqueness from their physical makeup, digital art exists as information, with the ability to be perfectly copied and disseminated. Perfect replication is recognized as a threat to the value held in traditional notions of authenticity, and technologies and theories have been made to mitigate this perceived issue within digital art. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are the most prevalent example of the counter against the threats posed by perfect replication. NFTs are defined by Kishore Vasan et al.(2022):

“A Non-Fungible Token (NFT) is a permanent and certifiable online record that connects a digital artwork, often called cryptoart, to its owner. enabling easy and fail-proof transfer of digital assets, and verifiable ownership of art. Hence, NFTs offer a mechanism for artists to create digital works of art and validate their work as unique, eternal, and worth collecting”(p.1).

Within their definition, they optimistically highlight the emergence and subsequent application of NFTs as a sure way to imprint ownership of digital art, and a way to make a defined piece of digital art as unique compared to its identical copies. Radermecker et al.(2023) directly questions the validity of this authority NFTs place upon a singular digital copy. Their work suggests that since digital art is able to be replicated perfectly, the validity in identifying one file as original cannot ever be certain. Since the work of the digital artist is mediated from person to form by a computer and distributed virtually, the certainty of identifying an original cannot be achieved. Even with an external validation, the defined original remains cognitively and technically indistinguishable from copies, and therefore holds no authority (Radermecker et al., 2023). This criticism is sound in logic, and exposes a blatant error in the logical reasoning behind the validity of NFTs.

The tension and absence of general consensus regarding the validity of attempts to make digital art definitive suggest that authenticity is a vital part in the materiality of art, and that there is a desire to place these values onto digital art. But ultimately, the attempt is futile, and the attempt put forth by NFTs has failed.

4.2 The Rejection of Replicability

Another form of mitigation concerning the nature of digital art’s ability to be perfectly replicated, and evidence to the importance of authenticity as an aspect of materiality in art, is the outright rejection of digital arts ability to be replicated. Walter Benjamin (1935) argued that an artwork's aura stems from its singular existence in time and space, a quality threatened by mechanical reproduction. Attempts to solidify digital art's value, as seen with NFTs, often strive for a kind of digital permanence, a desire to make digital art eternal (Vasan et al., 2022). Ironically, some digital art forms inherently reject replicability by emphasising the experiential and ephemeral as a medium. Interactive digital art, for example, relies on real-time physical audience participation, making each encounter unique and impossible to fully replicate. David Saltz (1997), when writing about the art of interaction, puts forth that the audience's encounter with a piece of interactive art uses the limitations of time and location as a medium, an aesthetic value. The aspect of authenticity contributing to materiality is imbued into interactive digital art as the works occupy defined spaces in physical space and time, providing authenticity in each instance of interaction.

4.3 Reframing Replication: Neo-Ukiyo-e

Jan Cao (2019) directly questions Benjamin’s theory regarding the withering of artistic value within replications by pointing out his own appreciation of a work which, unknowingly to Benjamin, was a work of mechanical reproduction. Benjamin uses a legend of a Chinese painter who stepped into his own painting and disappeared, as an example of a myth which proves the irreplaceable aura of traditional works of art. In her research, Cao determines that Benjamin’s understanding of this legend, and his appreciation derived from it, actually originates from a ukiyo-e illustration. Ukiyo-e is a Japanese method of woodblock printmaking which was so popular, it defined an art period throughout eighteenth-century Asia (Cao, 2019). The illustration which Cao determines to be the one Benjamin encountered, was created by a Japanese ukiyo-e printmaker, Tachibana Morikuni. Morikuni had himself likely copied his illustration from an earlier work, and his ukiyo-e of this legend was distributed in large numbers due to the popularity of the medium in Asia (Cao, 2019). If Benjamin can derive a sense of aura from a work of mechanical reproduction, then perhaps his ideas of artistic value may be subject to western biases. or perhaps these attempts at mitigating the effects of perfect replicability within digital art are limiting the capability to appreciate the extent of digital art’s aesthetic potential within our digital society. There lies an argument that digital art exists as a new form of ukiyo-e, that the very nature of its perfect replicability could be a valued aesthetic trait. This neo-ukiyo-e concept, reframes replication not as a detriment to authenticity but as a potential source of aesthetic value (Davis, 2023).

4.4 The Embrace of Replicability

Beyond the realm of formal digital art practices, the internet meme exemplifies a vernacular embrace of replicability. Memes, by their very nature, thrive on endless iteration and re-contextualization (Shifman, 2012). Memes frequently engage in a meta-commentary on the very nature of digital reproduction, often referencing the degradation of artistic reverence or the overwhelming saturation of imagery in the digital age. They are effective examples of neo-ukiyo-e. They are undoubtedly art.

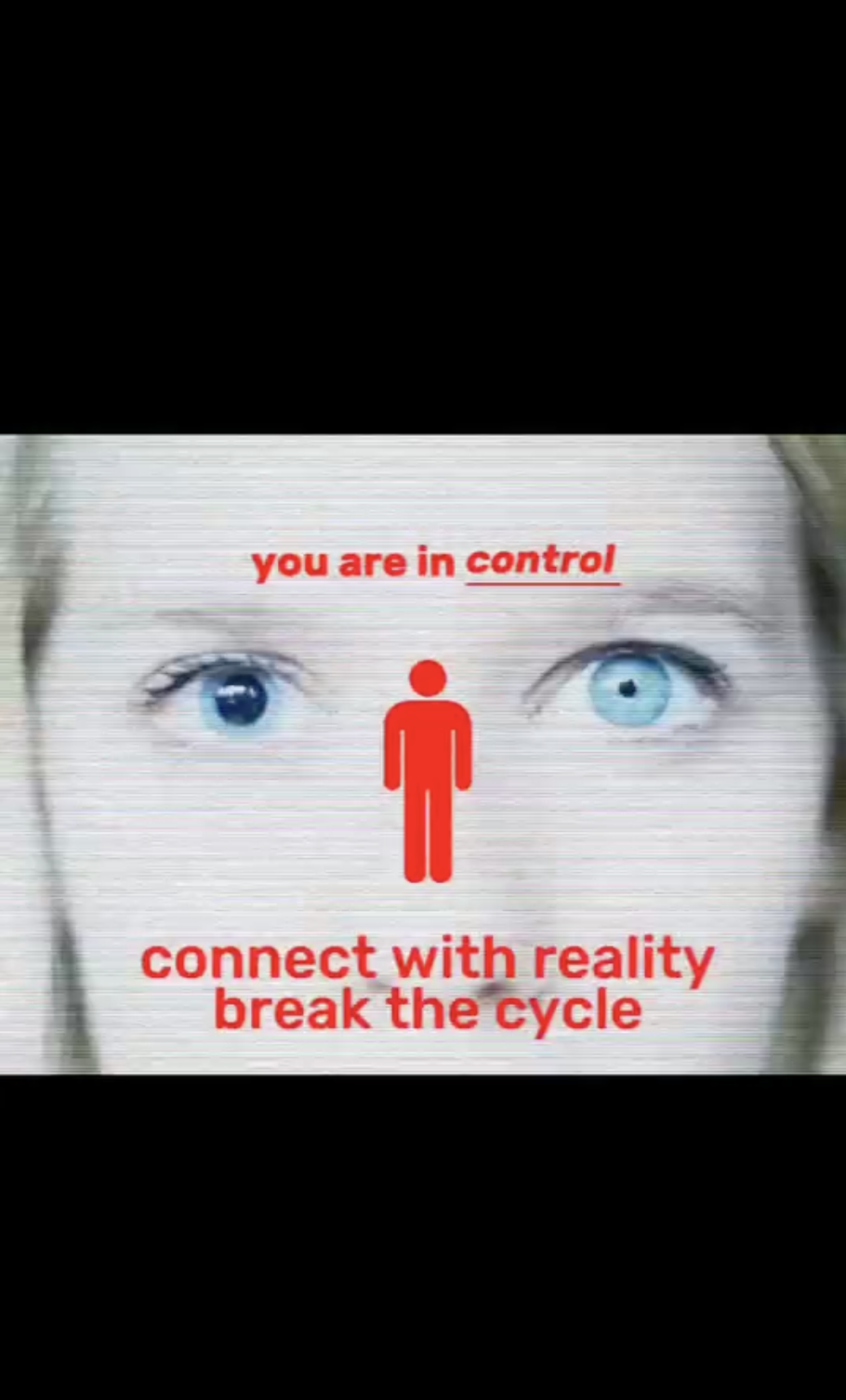

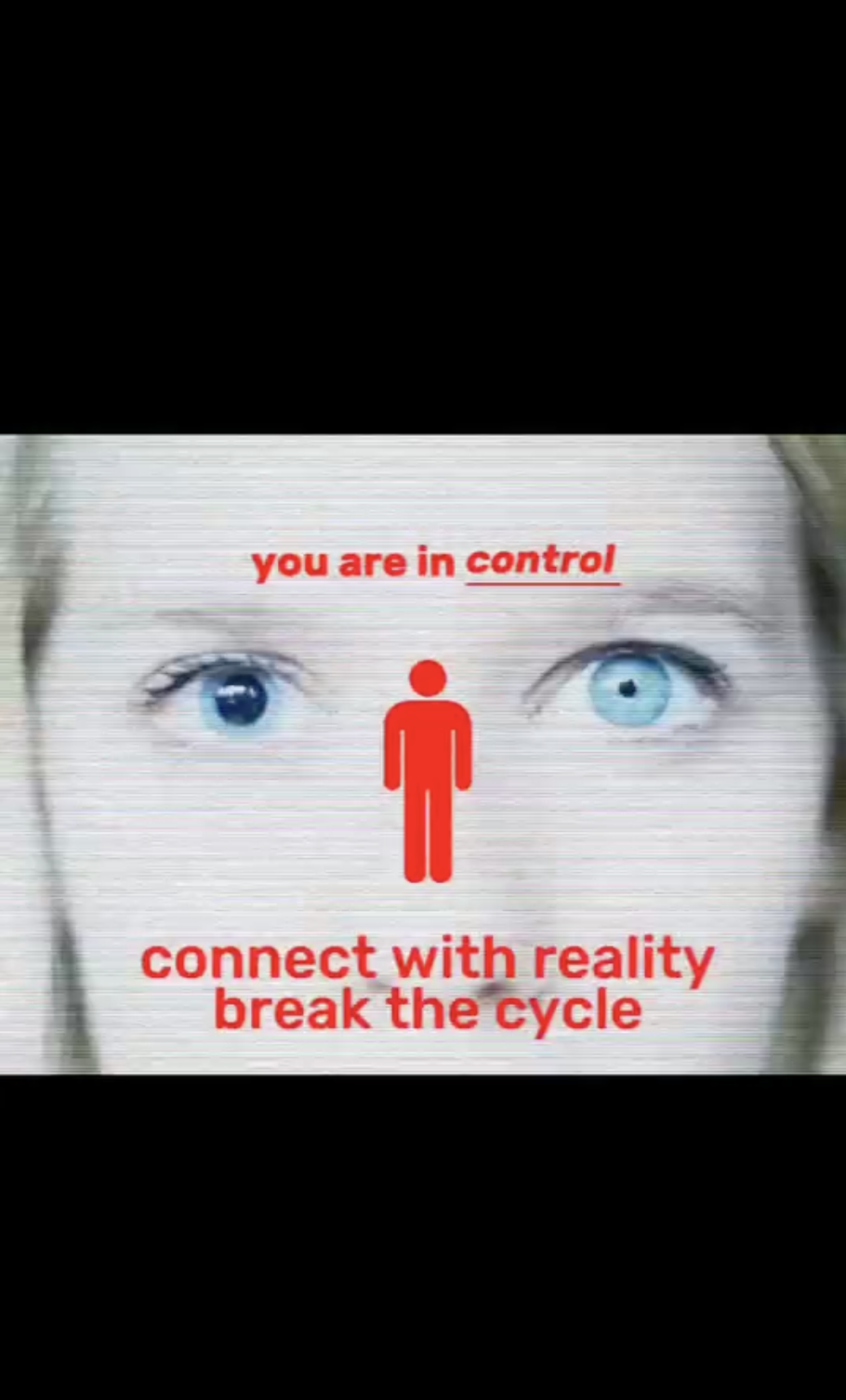

@blodheaven's Instagram Reel titled, thank you kalos (2024) (see Figure 1.), demonstrates re-contextualization. The work itself, a flashing image of eyes overlaid with the text "You are in control. Connect with reality and break the cycle," exists because of replicability. Its very form, designed for the endless scroll and rapid consumption of social media, is what allows it to reach viewers like @[gabriele_rafila], who comments, "I think… I’m going to uninstall Instagram." But the message itself is a direct confrontation of that replicability, a jarring call to break free from the hypnotic cycle of digital consumption. This inherent tension, the way the work utilises the very tools of mass reproduction to critique the act itself, highlights the complex and often contradictory relationship between art, value, and replication in the digital age.

Figure 1.blodheaven [@blodheaven]. (2024, July 10). thank you kalos [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C9OvHE1SJ7P/

@scrolling.end (2024) (see Figure 2) takes a different approach, utilising replicability to spark a moment of unsettling self-reflection. This Reel mimics in a prank-like manner, the familiar format of the Instagram app's "end screen," signalling there's no more content to consume. This simulated ending, however, becomes a prompt for more questions: Would we reflect on our time spent scrolling if a true end were ever reached? Would we feel embarrassed, or frustrated by the sudden lack of content? By replicating a on-brand UI element, the Reel disrupts the user's flow, forcing them to confront the potentially hollow nature of endless consumption. It presents a paradox of digital engagement: we crave the infinite scroll, yet the very idea of its ending exposes our unease with its implications.

Figure 2. scrolling.end [@scrolling.end]. (2024, August 4). [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C-rbi5GovBo/

@verylovingcat.jpg (2024) (see Figure 3) ventures further into the surrealist side of replicability, their work a digital echo of Dadaist absurdity (Prager, 2012). A typical-looking Instagram Reel devolves into a sustained wall of distorted visuals and white noise, stretched to the platform's maximum time limit. The humour lies in this very commitment to the absurd, mirroring the often overwhelming, nonsensical nature of the internet itself. @verylovingcat.jpg's work embraces this overwhelming absurdity, and transforms it into an aesthetic experience. It is a reminder that in the digital age, even nonsense can (or perhaps especially) be endlessly replicated, shared, and, in its own strange way, enjoyed.

Figure 3. verylovingcat.jpg [@verylovingcat.jpg]. (2024, July 26). [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C95gjS2vgxR/

This engagement with replicability suggests an aesthetic sensibility attuned to the unique conditions of digital culture. Just as the Surrealists sought to disrupt conventional modes of perception and representation, meme creators utilise the tools of mass reproduction to offer a distorted mirror to our digitally mediated reality (Prager, 2012). Further investigation into the specific visual and rhetorical strategies employed by memes could reveal a deeper commentary on the evolving relationship between art, value, and replication in the digital age.

5.0 DUST ARMOUR

From the recognition of fluid technologies and the experience of cyber-physical convergence, a realisation emerges that art may become like dust in the digital realm: insignificant and elusive. The impulse to safeguard digital art from this effect manifests in a phenomenon we might term: Dust Armour. This aesthetic approach seeks to imbue digital creations with a semblance of physical tangibility, often by drawing upon traditional notions of artistic value. Like artefacts encased in protective layers, these works may reference historical aesthetics, incorporate physical components, or attempt to artificially limit their reproducibility. In an attempt to imbue art with dust armour, the traditional understandings of materiality are preserved.

The rise of NFTs, while symptomatic of this desire for preservation, in their results ultimately fall short of true dust armour. By focusing solely on scarcity and ownership, NFTs neglect the deeper challenges of perfect replication and the evolving nature of the concept of materiality in a digital world. Dust armour, reflects a deep-seated anxiety about the perceived fragility of digital art and a reluctance to concede acceptance of new forms of materially.

Refik Anadol's artwork, while deeply entwined with AI, clings precariously to the edges of dust armour. His emphasis on the "decisive moment" acts as a defence against the scepticism associated with AI creation, reminding viewers that a human hand has set the system in motion (Waelder, 2023). This assertion of authorship, however, relies heavily on a carefully constructed context accessible only to a privileged few. The prestige of his gallery placements, the transparency of his data, and his ability to articulate his process in artist statements and interviews all contribute to a narrative of artistic control, forging a tangible link between Anadol's vision and the AI's output. However, this control he places emphasis on, is contingent on factors beyond the artwork itself. Should these external supports falter – the gallery system lose its authority, the artist statement become absent, or access to resources become unavailable – Anadol's work may suffer in the loss of materiality it holds, leaving his work vulnerable to the scepticism associated with AI driven art. This is not to say that Anadol’s works are to be criticised outright on the hypothetical removal of factors contributing to their materiality, but rather, Anadol’s work is an outlying case of success in using AI to achieve dust armour.

Dust armour is mostly exemplified in the medium of interactive digital art. In this medium, Each interaction becomes a unique moment in the artwork's lifespan, impossible to fully replicate or possess, highlighting the temporal and process-driven nature as something fundamental to the works of art. The Frame (https://dustarmour.com) is an example of this. As a hardware system for displaying interactive audio-visual art, it acts as a metaphorical protective enclosure, a controlled environment where the ephemeral nature of these interactions can be experienced and appreciated in the physical, even as they resist capture or ownership.

6.0 MOTH MEDIA

In contrast to the preservationist impulses of dust armour, moth media offers a different aesthetic perspective, one that recognizes and even celebrates the ephemeral nature of digital art. Like that of a moth, whose novelty and beauty is no less for its fleeting lifespan, digital creations possess their own inherent value within the framework of their impermanence. This perspective acknowledges and concedes to the reality that human experience itself will continue to be intertwined with the digital realm, suggesting new forms of materiality will form.

Moth media defines a category of digital art that embraces, rather than resists, the ephemeral nature of the online world. Like the fleeting beauty of a moth, these works find meaning and impact not in permanence, but within the constant flow of digital information and experience. To be considered moth media, a work must be digitally native, leveraging the unique affordances of online platforms. It acknowledges its own impermanence, existing comfortably within a fluid temporality where content is constantly overwritten, forgotten, or scrolled away from. Crucially, moth media sees replicability as a feature, not a flaw. Copying, sharing, and recontextualization become intrinsic to the work's existence and meaning, often encouraging iterative creation, or critical commentary on digital culture itself. Finally, these works often exhibit visual or conceptual qualities specific to the digital realm, such as glitch art, internet vernacular, or responses to the unique constraints and possibilities of online platforms.

Figure 4. Jahangir, A. [@AmaanJah]. (2023, November 2). fool's paradise [Post]. X. https://x.com/AmaanJah/status/1720206106826248558

Amaan Jahangir's fool's paradise (2023) (see Figure 4) , a painting of a jester superimposed over a screenshotted image of an iPhone Messages search result of "I love you", exemplifies the essence of moth media. The artwork's very form, a digital image posted to X.com (formerly Twitter.com), speaks to the nature of materiality in the digital world. Its lowercase title subverts the traditional reverence for titles and documentation in art, while reflecting the blasé passivity often associated with online engagement. Jahangir's piece directly confronts the complexities of online relationships, contrasting the overwhelming volume of search results for "I love you" with the implied failure suggested by the title and the jester's obscuring presence. By utilising a text message feed as both subject and medium, and by disseminating the work through social media, "the fool's paradise" not only comments on its digital environment, but also leverages it as an intrinsic part of its existence. The artwork's journey, with its source material originating from a smartphone and ultimately received on countless others, further blurs the lines between creation, consumption, and context and actively uses this as an aesthetic choice.

The Instagram Reel You will NOT believe what happens in the end!!... by @happinesseverydayimhappy (2024) (see Figure 5.) exemplifies moth media, not just through its digital format, but through its commentary on the very nature of online existence. As a work of moth media, it embraces ephemerality, replicability, and the aesthetics of the digital, to deliver the intent of the artist. The title itself, with its clickbait phrasing and encouragement to share, embodies the rapid, attention-grabbing, and participatory nature of short-form video content. This fleeting quality is further emphasised through the work's quick cuts, glitching VHS effects, and evolving imagery. Within this ephemeral framework, the artist tackles complex themes of voyeurism and digital anxiety. The "satisfying" video which the Reel poses as initially, quickly descends into unsettling imagery. Text like "I see you" and the emergence of a glitching human figure taps into the feeling of being watched . By juxtaposing these horror themes with the seemingly mundane format of an Instagram Reel, @happinesseverydayimhappyhighlights how deeply intertwined these digital anxieties are with our everyday lives. In doing so, the work directly uses the saturation brought forth by fluid technologies as a prominent factor in its materiality. Not only does the work reference fluid technologies in its subject matter, but uses them also as a medium

In the act of creating works of moth media, traditional understandings of materiality may still be obscured, but the factors which obscure them, are instead used as a form of materiality themselves. Moth media encourages us to shift our focus from permanence to presence, appreciating the experience of digital art in the moment, even as it evolves, transforms, or fades away. It is an invitation to find beauty and meaning not in spite of, but because of, the shifting familiar forms of materiality.

Figure 5._happinesseverydayimhappy [@happinesseverydayimhappy]. (2024, July 26). You will NOT believe what happens in the end!! Tag someone who agrees and share this with someone who you think needs this! [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C95ateiRwil/

7.0 RIVULET, A CONCLUSION

The exploration of materiality in the context of digital art reveals a dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation. Rivulet (dustarmour.com) serves as an example of this duality, functioning both as an interactive art piece and a short-form video which references the ephemeral qualities of moth media while simultaneously engaging with the preservationist impulses of dust armour. In its short-form video format, Rivulet is only one second long, forming a perfect loop of an endless stream of moths moving upward and offscreen. The extremely short duration is intentional on two fronts. First, it is a subversion of the expected quick satisfaction sought after in the short-form video format, suggesting that it is a conscious choice to remain on the video past its full run time. Second, this piece is short in duration to act as a trick, generating a substantial amount of recorded views per interaction compared to a typical short-form video, and using the social media where it exists as a contribution to its aesthetic choice. The work in its interactive art form, is displayed within the Frame system (dustarmour.com). As users approach the work, their motions trigger subtle visual differences. Different proximities, and gestures, trigger different sustained notes in a harmonic chord. However, if an audience member takes out their phone in the proximity of the sensors, the image becomes distorted and a dissonant note rings out. The moths, floating upward endlessly, mirror the fleeting nature of digital art. In essence, Rivulet is the culmination of this thesis’ assertion the need for a nuanced understanding of materiality that embraces the complexities of contemporary artistic expression, inviting a broader appreciation of the beauty and significance found within the still young world of digital art.

APPENDIX A

Figure 1.blodheaven [@blodheaven]. (2024, July 10). thank you kalos [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C9OvHE1SJ7P/

Figure 2. scrolling.end [@scrolling.end]. (2024, August 4). [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C-rbi5GovBo/

Figure 3. verylovingcat.jpg [@verylovingcat.jpg]. (2024, July 26). [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C95gjS2vgxR/

Figure 4. Jahangir, A. [@AmaanJah]. (2023, November 2). fool's paradise [Post]. X. https://x.com/AmaanJah/status/1720206106826248558

Figure 5._happinesseverydayimhappy [@happinesseverydayimhappy]. (2024, July 26). You will NOT believe what happens in the end!! Tag someone who agrees and share this with someone who you think needs this! [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C95ateiRwil/

REFERENCES

Almenberg, G. (2010). Notes on participatory art: Toward a manifesto differentiating it from open work, interactive art and relational art. AuthorHouse.

Benjamin, W., & Jennings, M. W. (2010). The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility [first version]. Grey Room, 39, 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1162/grey.2010.1.39.11

blodheaven [@blodheaven]. (2024, July 10). thank you kalos [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C9OvHE1SJ7P/

Brown, P. (2005). Is the future of music generative? Music Therapy Today, 6(2), 215-274.

Bruck, J., & Docker, J. (1991). Puritanic rationalism: John Berger's Ways of Seeing and Media and Culture Studies. Theory, Culture & Society, 8(4), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327691008004004

Cao, J. (2019). Benjamin's Chinese painter: Copying, adapting, and the aura of reproduction. The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory, 94(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00168890.2018.1548423

Carroll, N. (1986). Art and interaction. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 45(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.2307/430466

Davis, J. (2023). A brief inquiry into the tangibility of digital art [Unpublished manuscript]. The Creative School, Toronto Metropolitan University.

De Smedt, J., & De Cruz, H. (2011). A cognitive approach to the earliest art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 69(4), 379–389. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23883686

Debord, G., Perlman, F., & Knabb, K. (2021). The society of the spectacle (1st ed.). Critical Editions.

Dewey, J. (1958). Art as experience. Capricorn Books.

Dust Armour. (2024). Dust Armour. https://www.dustarmour.com

François, J.C. (1990). Fixed timbre, dynamic timbre. Perspectives of New Music, 28(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/833012

Frascina, F. (1983). Modern art and modernism: A critical anthology. Taylor & Francis Group.

Gradim, R., & Pestana, P. D. (2021). Overview of generative processes in the work of Brian Eno. 11th Workshop on Ubiquitous Music (UbiMus 2021), 45-56.

Gurtala, J. C., & Fardouly, J. (2023). Does medium matter? Investigating the impact of viewing ideal image or short-form video content on young women's body image, mood, and self-objectification. Body Image, 46, 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.06.005

Hainge, G. (2002). Platonic relations: The problem of the loop in contemporary electronic music. M/C Journal, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1974

Herbert, R. (2007). Impressionism, originality, and laissez-faire. In M. Tompkins Lewis (Ed.), Critical readings in impressionism and post-impressionism: An anthology (pp. 23-30). University of California Press. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/10.1525/9780520940444-003

Hodkinson, J. (2017). Playing the gallery. Time, space and the digital in Brian Eno's recent installation music. Oxford German Studies, 46(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/00787191.2017.1345435

Jahangir, A. [@AmaanJah]. (2023, November 2). fool's paradise [Post]. X. https://x.com/AmaanJah/status/1720206106826248558

Jenkins, H. (2014). Rethinking 'Rethinking Convergence/Culture'. Cultural Studies, 28(2), 267-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2013.801579

Kant, I., & Walker, N. (2007). Critique of judgement. Oxford University Press.

Lyons, J. (1967). Paleolithic aesthetics: The psychology of cave art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 26(1), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/429249

Lojdová, Š. (2019). Stephen Snyder, End-of-Art Philosophy in Hegel, Nietzsche and Danto. Estetika (Praha), 56(2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.33134/eeja.193

McLuhan, M. (1964, 2013). Understanding media: The extensions of man (Critical ed.). Gingko Press.

Mills, C. M. (2009). Materiality as the basis for the aesthetic experience in contemporary art [Master's thesis, University of Montana]. ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1289

Montag, C., Yang, H., & Elhai, J. D. (2021). On the psychology of TikTok sse: A first glimpse From empirical findings. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 641673–641673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641673

Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology after the end of the world (1st ed.). University of Minnesota Press.

Prager, P. A. (2012). Making an art of creativity: The cognitive science of Duchamp and Dada. Creativity Research Journal, 24(4), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.726576

Radermecker, A. V., & Ginsburgh, V. (2023). Questioning the NFT "Revolution" within the art ecosystem. Arts, 12(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12010025

Rau, C. (1950). The aesthetic views of Jean-Paul Sartre. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 9(2), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.2307/426334

Saltz, D. Z. (1997). The art of interaction: Interactivity, performativity, and computers. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 55(2), 117. https://doi.org/10.2307/431258

Shifman, L. (2012). An anatomy of a YouTube meme. New Media & Society, 14(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811412160

scrolling.end [@scrolling.end]. (2024, August 4). [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C-rbi5GovBo/

Siemens, E. (2021). "It's You Plus It's … Art": The #Artselfie debate from Douglas Coupland to Tolstoy. Canadian Review of Comparative Literature / Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée, 48(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1353/crc.2021.0002

Stevenson, A. (2024). The performance of machine aesthetics: Acoustic reimagining of electronic music. Popular Music, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026114302400014X

Stroh, K. M. (2015). Intersubjectivity of Dasein in Heidegger's "Being and Time": How authenticity is a return to community. Human Studies, 38(2), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-015-9341-9

Tousley, N. (2011, January 11). Marrying music and images; Brian Eno's 77 Million Paintings is a meeting place for creating 'democratic popular art'. Edmonton Journal.

Vasan, K., Janosov, M., & Barabási, A. L. (2022). Quantifying NFT-driven networks in crypto art. Scientific Reports, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05146-6

verylovingcat.jpg [@verylovingcat.jpg]. (2024, July 26). [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C95gjS2vgxR/

Waelder, P. (n.d.). Refik Anadol: Art in a latent space. Niio. https://www.niio.com/blog/refik-anadol-art-in-a-latent-space-2/#:~:text=Refik%20Anadol%3A%20%E2%80%9Cthe%20most%20important,%2C%20and%20that%20can%20dream.%E2%80%9D

Watson, A., Watson, J. B., & Tompkins, L. (2023). Does social media pay for music artists? Quantitative evidence on the co-evolution of social media, streaming and live

music. Journal of Cultural Economy, 16(1), 32–46.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2022.2087720

West, R., & Burbano, A. (2020). AI, arts & design: Questioning learning machines. Artnodes, 26, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.7238/a.v0i26.3390

_happinesseverydayimhappy [@happinesseverydayimhappy]. (2024, July 26). You will NOT believe what happens in the end!! Tag someone who agrees and share this with someone who you think needs this! [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C95ateiRwil/